By William P. Marchione, Ph.D., author of A Brief History of Smyrna, Georgia (2013), and the Chair of the Smyrna Historical Society’s Research Committee

The following article summarizes the conclusions I reached in my February 2020 Black History Month lecture on the history of race relations Smyrna.

The single most striking conclusion that I reached was that Smyrna’s white political establishment had engaged in a quarter century-long effort to expel Smyrna’s blacks from the city, to in effect, “whiten” Smyrna..

*African-Americans comprised about 13% of the population of Smyrna at the time of its incorporation as a city in 1872. This small, powerless element was exploited and subordinated from the outset. This becomes abundantly clear when one examines of the city’s federal census schedules for the period 1880 to 1920.

*Of the ten black households in Smyrna in 1880 (that being the first census providing a clear picture of city’s racial composition) not one black head of household owned the land on which he resided (eight were headed by tenant farmers, one by an employee of a blacksmith, and another by a laundress).

*The census of 1900 (conducted after an 1897 reduction in the size of the city to one quarter of its former size) showed no improvement whatever in the socio-economic status of Smyrna’s black population, but rather a decline. In 1900, of the nine black households that lay within Smyrna’s now greatly reduced boundaries, five were headed by women all of whom earned their livelihood as domestic servants—laundresses, cooks, and maids, while the remaining heads of household, headed by males, were listed as farm laborers and tenants.

*Even in 1920, a half -century after the Civil War, despite years of economic prosperity for the city as a whole, blacks had still made no appreciable socio-economic progress. Smyrna was experiencing the beginning stages of suburbanization in these years—an increasing degree of prosperity fostered by a combination of major transportation improvements (the installation in 1905 of a streetcar that ran from Atlanta through Smyrna to the county seat, Marietta, with multiple stops in Smyrna; increasing motor vehicles ownership; and the absorption of the town’s main thoroughfare [Atlanta Road] into the interregional Dixie Highway linking Florida to the Midwest). The decade of the 1920s was for Smyrna a period of significant economic well-being. But for the African-Americans element of the population little had changed.

*That the community’s black population remained in thrall to its white population (a state of affairs described by one author as “slavery by another name”) is evidenced by an incident that occurred at Wikle’s Drugstore in downtown Smyrna in the final months of World War I when several black youths had the temerity to attempt to buy ice cream cones using the store’s front entrance rather than its back door. They were not only denied service by the proprietor, but were set upon by the local police in an incident that resulted in one of the offending young men being shot in the leg by a policeman.

*Instead of social progress, what the decade of the 1920s witnessed was the adoption by the city of a series of ordinances and policies calculated to drive black out of the city altogether—the beginnings of a sustained effort to exclude and isolate blacks that became increasingly overt and ugly over the years.

* In 1920 the black population of Smyrna stood at just 17 households, a smaller percentage of the total population than had been the case back in 1880. By 1920, moreover, most of Smyrna’s black households were concentrated in a depressed neighborhood lying just south of Spring Street, chiefly along Elizabeth Street and an intersecting pathway commonly referred to as “Railroad Alley,” that lay adjacent to the tracks of the old W&A Railroad.

*These were also the years in which the second Ku Klux Klan was at the height of its baleful influence, attaining a national enrollment of some 6 million members, with its national headquarters located in nearly Buckhead, a mere eight miles south of Smyrna. As a secret order, the members cannot be identified individually but regional patterns make it likely that by 1920 most, if not all, of Smyrna’s city officials, its Mayor, City Council members, and its School Board were among the Klansmen who marched regularly through the black section of town in an effort to intimidate Smyrna’s relatively unoffending African-American community.

*The degree of racism that prevailed in Smyrna is further attested to by two political events of the first quarter of the 20th century, the first being the election of one Jake Moore as mayor, in 1910 and again in 1911. Moore, a former superintendent of the state penitentiary had been deeply implicated in the notorious convict labor scandal of that period, leading to his resignation from that post. His election as Mayor, not once but twice (he died in office) attests to the deep racial biases that then prevailed in the city.

*Then in the mid-1920s, Smyrna elected another overtly racist Mayor, J. Gid Morris. It was an incident on this man’s Marietta farm in the late 1890s (he had earlier served as mayor pro-tem of Marietta) that precipitated one of Cobb County’s three recorded lynchings. In addition, Fred Morris, J. Gid’s son, who served as Smyrna’s City Attorney during his father’s mayoralty, was a party to the notorious lynching of Jewish merchant Leo Frank in nearby in Marietta in 1915. The Klan, it should be remembered, not only targeted Blacks, but outsiders in general, especially immigrants and Jews.

*The intensity of Morris’ racism is evidenced by the following impassioned outburst in an address he delivered to a Confederate veterans group in Columbus, Georgia in 1905, in which he condemned President Theodore Roosevelt for inviting black educator Booker T. Washington to dine at the White House:

[Roosevelt] can eat, drink, and sleep with them, Morris fulminated, and none can hinder, but when he has gone to the sun and with his feeble breath blown out the light that illumines the world, then will I believe that he can inaugurate some plan by which you, my fellow countrymen, will be willing to sit with your wives and daughters at the same table with a negro, or submit to negro equality whatever.

*By 1927, Smyrna’s town government made its commitment to residential segregation explicit by adopting an ordinance stating that no black person might occupy a dwelling closer than 200 yards from that of a white person. This ordinance was not uniformly enforced out of deference to the many white property owners renting to black tenants. However, the trajectory of the city’s policy of exclusion was set by the adoption of this ordinance. In the 31 years that followed Smyrna’s blacks were systematically harried out of city, some of them, as we shall see, choosing to take up residence in a neighborhood about a mile and a half east of Smyrna’s city limits called Davenport Town.

*Further evidencing this policy of exclusion was the rejection by the City of Smyrna of a petition of the black residents of the Elizabeth Street/ Railroad Alley neighborhood asking permission to build a church on Elizabeth Street. With the rejection of this application, the city’s blacks were obliged to construct their house of worship, not in the neighborhood where they chiefly resided, but on a parcel of land lying outside of the city’s corporate limits, on Hawthorne Avenue. That church, The Mount Zion Baptist Church, functioned not only as a house of worship for the blacks of the area, but also as a school (none then existing for the blacks anywhere near Smyrna), with a portion of the grounds set aside for burials. Churches were the central institutions in black communities.

*Also, in 1927, a prominent local citizen, Nathan Truman Durham, petitioned the city to invoke its housing segregation ordinance to expel the blacks tenants then residing on Elizabeth Street on the grounds that his wife, Lizzie Phagan Durham, the aunt of the young girl, Mary Phagan who had been murdered in 1913 in the Atlanta pencil factory managed by Jewish merchant Leo Frank, could not abide having blacks living near her. The Durhams resided in a house that still stands at the corner of Spring and Elizabeth Streets, near the Elizabeth Street/Railroad Alley black enclave.

* While the city refused to order the wholesale expulsion of African-Americans from Elizabeth Street, as Mr. Durham had demanded, it did authorize the eviction of the black tenant who lived closest to the Durham residence, and also ordered Claude Osburn, the white owner of the Elizabeth Street rental properties, to “open up a private street at his own expense for exit and entry of Negroes in that vicinity” so as to eliminate the unwelcome comings and going of blacks by the Durham residence.

*Another aspect of the history of the area that I was able establish through a analysis of the 1920 to 1940 federal census schedules, is that the Davenport Town black enclave came into existence as a by-product of this policy of exclusion. In 1920, before the adoption of this ordinance, only one black family resided in the area that would afterwards be designated “Davenport Town” (near the present-day intersection of Hawthorne Avenue and Davenport Streets), a family of twelve headed by a tenant farmer named Henry W. Davenport, who would later serve for many years as minister of the Mt. Zion Baptist Church. The population of this black neighborhood grew rapidly in the aftermath of the 1927 ordinance. It rose from a mere 12 residents in 1920 (all members of the Davenport family) to 25 by 1930, reaching 75 by 1940.

*The next notable incident impacting Smyrna’s black community came in 1938, when the murder of a white farmer, George Washington Camps and his daughter, Christine Camp Pauls by Willie Drew Russell, an inebriated black laborer who had apparently sought without success to collect unpaid wages from Camps, his sometimes employer. An altercation followed in which an infuriated Russell murdered Camps and Paul. That murder, which occurred in the countryside three miles west of downtown Smyrna, precipitated a riot in which 500 or more whites attacked blacks indiscriminately, dragging them from streetcars and automobiles and attacking their residences (again mostly white-owned rental properties) driving many of them from the area in abject terror. Several black families were still living in the Elizabeth Street neighborhood at this juncture. These properties were systematically attacked and damaged. The rioters also torched a school building that had recently been constructed by Cobb County for blacks adjacent to the Mount Zion Church, this being the first publicly financed “colored” schoolhouse built anywhere in the vicinity.

*Among the white rioters were some of the leading citizens of the town, including Cobb County Surveyor Paul Hensley, and Marcus Parnell, a prominent dairyman. While several men were arrested for participation in this 1938 riot, only one was convicted and jailed, an adolescent who was said to be mentally retarded.

*At least one Smyrna resident came to the defense of local blacks in this incident. Property owner Nina Ruff Beshers, a member of the prominent Ruff family, who is reputed to have kept the mob from attacking some of the the houses occupied by black tenants, which lay behind her residence on Atlanta Road.

*While the local press sought to downplay the significance of this riot, suggesting that the perpetrators were outsiders, the incident attracted substantial national attention that sullied Smyrna’s reputation. A newspaper article published in a black paper in the mid-west described the 1938 Smyrna Race Riot in these terms:

Rioters would pull Negroes from their cars as they traveled along Highway 41 [Atlanta Road] and beat them. Negroes also were pulled from streetcars and beaten, Mrs. Beshers said. The rioters were also coming down Elizabeth Street after Smyrna’s Negro residents when the woman herself stopped the drunken white leader [possibly Cobb County Surveyor Hensley who was later charged with drunkenness] with threats of using a shotgun she had. The removal of blacks from the area was not connected with the trouble, she said. Their black tenants moved only when her husband sold the property.

*In the years that followed this 1938 race riot, the color line solidified. In 1951, Cobb County ordered the relocation of the Mount Zion Baptist Church from its original site on Hawthorne Avenue into the heart of Davenport Town, a half-mile further east, the original site having been designated by Cobb County by that date as “a white section.”

*The expulsion of blacks from Smyrna and their gradual relegation to an area well outside the city would seem to have reached its culmination in November 1958 when The Marietta Journal reported that the last three black residents of Smyrna had been ejected from the city after being adjudged guilty of operating a “disorderly house.” Smyrna’s town booster’s could and did now claim that the city had no black residents, a state of affairs that the city’s leadership presumed would foster land and real estate values at a time when whites were moving out of Atlanta into suburban locations in increasing numbers (so-called white flight) and also moving into Smyrna near the massive Lockheed Aeronautics plant, the largest industrial facility in the state, a facility that furnished in excess of 30,000 jobs.

It thus took a quarter century for the city to fully implement the policy initiated by the 1927 housing segregation ordinance, doing so just in time to accommodate the major spurt of residential expansion that Smyrna was experiencing by the mid-1950s.

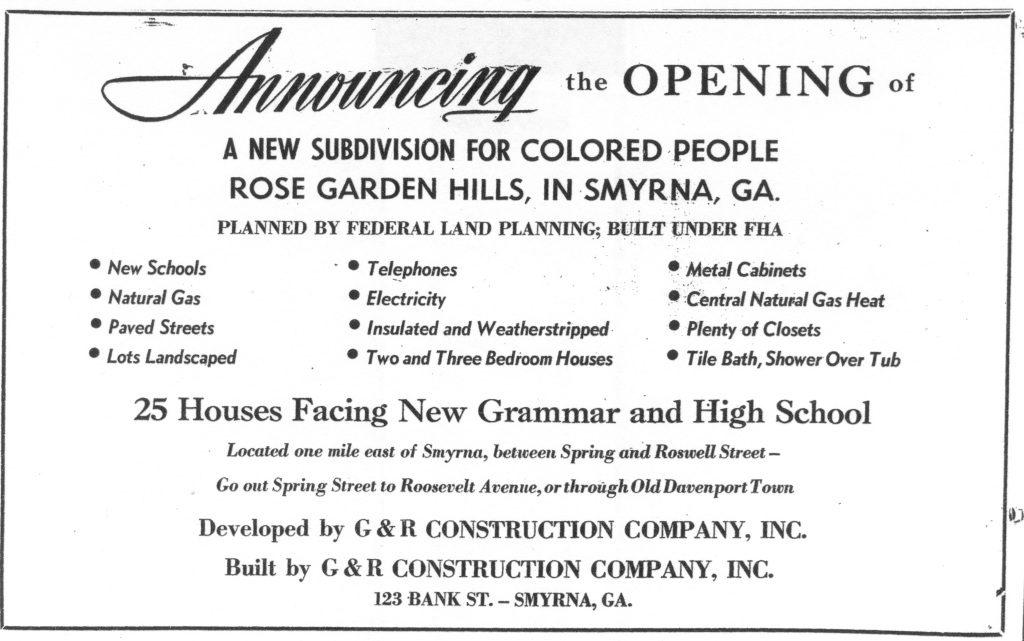

*The next major development in the history of Smyrna’s black community was the building in the years after 1953 of a new, racially-segregated housing development for middle class blacks called Rose Garden Hills, situated on a parcel of land adjacent to Davenport Town.

*This project was the brain child of former and future Smyrna Mayor J. M. “Hoot” Gibson in partnership with real estate developer Bill Reed, operating as the G&R Construction Company. .

*As is often the case with real estate projects, the quality of the subdivision fell somewhat short of what its projectors had promised, especially from the standpoint of sanitation and basic public services. While Smyrna had recently installed a much-improved water supply and sewerage system, none of of the Rose Garden Hill properties, lying as they did outside the city, had access to these services, and thus within a few years the neighborhood developed serious drainage and public health problems.

*A central component of the Rose Garden Hills subdivision, however, was a modern (albeit segregated) schoolhouse.

I was told by Mark Reed, son of developer Bill Reed, that former Mayor Gibson and his father were criticized by many white residents of Smyrna for bringing this middle class black element into the area, but it must again be emphasized that Rose Garden Hills lay outside of Smyrna’s city limits and that its residents were accordingly unlikely to have much daily contact with the city’s white population, except as a source of cheap labor. When I asked a lifelong resident of Smyrna, a man in his mid-seventies, what he could remember from his youth about Smyrna’s black community, he answered, “We were hardly aware that it existed.”

*It must again be emphasized that these blacks (living as they did outside of Smyrna’s corporate limits) had no access to the municipal services that the fast growing city was offering its white residents: such amenities as fire protection, police protection, an ample water supply, sewerage, access to parks, to the city’s public library, to its recreational facilities, or the city’s newly established teen center.

*This dearth of basic services could have been resolved by the simple expedient of annexing the Rose Garden Hills section to the city, but Smyrna’s white leadership staunchly opposed absorption of this black neighborhood into Smyrna for the next four decades.

*One of the reasons that the Smyrna Public Library (which the city had provided with a modern building in 1961) rejected a Cobb County invitation to join its developing library system was almost certainly the Jonquil City’s intensifying commitment to racial segregation. In 1969, Smyrna Mayor George Kreeger, the dominant political figure in Smyrna in the decade of the 1960s, declared in unvarnished terms, Negroes will not be let into the city—Rose Garden Hills will not be annexed!

*The U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954 provided the entering wedge for integration. Agitation for integrated school facilities began in the wake of that decision, but met unremitting resistance for years after from the area’s white leadership.

*Notably, the KKK took on renewed energy in these years. Even Raymond Reed, a relatively progressive state representative, who held office in the late 1940s and 1950s and took brave stands against the Klan (sponsoring legislation to unmask the order and strongly opposing private ownership of Georgia’s public schools) never explicitly advocated integration. No local politician dared to take racism on so blatantly. To have done so would have spelled political disaster. Most of Smyrna’s elected officials were in fact stout segregationists. Reed’s retirement from elective politics in the late 1950 was almost certainly occasioned by this rising tide of anti-black sentiment which crested in the late 1950s and early 1960s. These were the years that saw the election of three successive race-baiting Georgia governors—Talmadge, Griffin and Vandiver. Segregation Forever! was their clarion call.

*The Cobb County Schools remained segregated until the mid-1960s, and were thereafter integrated on a phased-in basis. Even with the coming of integrated school facilities the area’s blacks lacked access to the municipal services the developing commuter suburb of Smyrna was then offering its residents, services Cobb County could not provide its residents

*Only in 1983, during the administration of Mayor Arthur Bacon was the Rose Garden Hills neighborhood absorbed into Smyrna. It took another decade for the city to annex the older and less desirable Davenport Town neighborhood, then referred to pejoratively as The Hole—a poorly served, run down area surrounded on all sides by the fast-developing City of Smyrna.

*Smyrna’s motivation for annexing these black enclaves needs to be understood for what it was. These annexations were not carried out from a dawning sense of social justice. The 1983 annexation would seem to have been related instead to the absorption of a sizeable tract of land lying just east of the Rose Garden Hills community, the parcel through which Village Parkway was being projected, highly desirable acreage that added appreciably to Smyrna’s tax base and also served to block the City of Marietta’s rapid expansion southward.

*The 1993 annexation of the older Davenport Town section, was motivated by a need to place that neglected enclave under the jurisdiction of the Smyrna’s police, to ensure that this neighborhood, now completely surrounded by Smyrna, would not jeopardize the development potential of the surrounding acreage and thereby impede Smyrna’s emergence as one of Atlanta’s “preferred suburb.”

*It should be noted that the 1993 annexation of “The Hole” coincided with Smyrna’s Downtown Redevelopment Project, consonant with the transformation of Smyrna from the “redneck town,” as it had been described in a controversial 1988 National Geographic Magazine article, into the upper class suburb it was in process of becoming by the early 1990s. In short, economic considerations calculated to sustain and enhance real estate values and remove impediments to “quality” development were the chief motivating factors behind these annexations.

*One other aspect of the history of this neighborhood that warrants attention was the singular leadership provided by school teacher and school principal Tom McNeal. McNeal first appeared on the scene in 1956, when he was designated an “outstanding teacher” in one of Cobb County’s black schools. McNeal, who settled into the Rose Garden Hill neighborhood, gradually emerged as that community’s primary leader and spokesman. By 1970 he was serving as Assistant Principal of the Nash Junior High School; then as Principal of the newly constructed Hawthorne Elementary School (close by Davenport Town), rounding out his long career in public education as the Principal of the Rose Garden Hills Elementary School, a position he held for a dozen years. None of these positions, it should be noted, was municipal. McNeal made his career as an employee of Cobb County.

*A 1970 Marietta Journal article tells us that McNeal taught high school in Florida prior to locating in Georgia; that he graduated from Florida A&M, did graduate work at Northwestern University and at the Tuskegee Institute, capping his education with a master’s degree from Atlanta University.

*McNeal was a man of many parts. A part-time contractor, he built several houses in the Rose Garden Hills neighborhood, including one for himself and his family on Teasley Drive. He also helped provide recreational activities for black youth in the days before integration. He was politically shrewd, ingratiated himself with Smyrna’s white politicians, mixing drinks at their political gatherings and at the American Legion Post, even serving for a time as maître d at Smyrna’s plantation-themed Aunt Fanny’s Cabin Restaurant. In the early 1980s he organized a local men’s club and spearheaded a cleanup campaign in Davenport/ Rose Garden Hills, and then became that community’s leading annexation advocate.

*While McNeal aspired to public office, seeking election three times, first to the Cobb County School Board and then the Smyrna City Council both in 1985 and 1987, he never came close to winning. While many more blacks were residents of the city by 1983, in the aftermath of the annexation of the Rose Garden Hills section, they still comprised only a small fraction of Smyrna’s electorate. Thus the political color line held firm.

*When I first arrived in Smyrna beck in 2009 one long-term resident informed me that she had been told that the members of the City Council had taken a pledge, presumably back in 1983, the year Rose Garden Hills was annexed, to do all that they could to prevent an African-American from ever sitting on Smyrna’s City Council. Another well-informed citizen told me that the City Councilor who represented Ward 3, the ward in which the black Davenport/ Rose Garden Hills neighborhood was situated, was given to racial epithets in conversation, thus hardly a figure who could be relied upon to champion the interests of his black constituents. Smyrna’s black community was thus without a political voice in these years.

*Only with the rise of the city’s black population to 31% in 2017 would Smyrna finally succeed in electing its first African-American City Council Member, Maryline Blackburn, a former beauty queen and entertainer. She won by a comfortable margin in a special election, but failed of reelection in 2019.

*At that point, in sharp contrast to the situation in Tom McNeal’s day, a substantial percentage of Smyrna’s population was black, with significant numbers of Hispanics and Asians also living in the city. By 2017, whites actually comprised a minority of Smyrna’s population, only 45 percent, though not necessarily of its registered voters. Thus the election of Smyrna’s first black City Council member occurred in a far different demographic context from the one that confronted Tom McNeal in the 1980s.

*Then a second black, Dr. Lewis Wheaton, a biology professor from Georgia Tech, was elected to the Smyrna’s City Council from Ward 7 in the southern part of Smyrna.

*Even more amazingly, in 2019, a kind of political annus mirabilis for Smyrna’s African-Americans after so many years in the political wilderness, a 26 year old black businessman and restaurant owner, Ryan Campbell, cobbled together a grass roots campaign for mayor that came within 159 out of 7,500 votes of defeating incumbent City Council Member Derek Norton, long-serving Mayor Max Bacon’s choice of a successor. This near miss represented a volcanic political development in a city that had for so long and so fervently resisted racial integration.

William P. Marchione, PhD. has written a powerful and probing article, of excellent scholarship, that opens up a painful and sad history that begs to be faced and considered. Fortunately, we are left with some rays of hope. Thank you.

LikeLike

Dr. Marchione, PhD. depicts a long term pattern of outrageous rules, deeds and violent actions

implemented against Black people. Fortunately, our current climate with an emphasis on a massive support of ‘BLACK LIVES MATTER’ movement I think America is making a pivotal movement in the direction of civility and equal treatment for all.

LikeLike

I’m very much encouraged by the recent Black Lives Matter movement and most importantly, it’s

diversity. To be honest, I was shocked and surprised by it. Historians. like Dr. Marchione, have played a major role in this progress by sharing the bare ugly truths of our country’s complicated history. Obviously, more white people are becoming more educated and find it hard to accept racism and inequality as being right and will serve our country well in the future.

LikeLike