The following photo essay, presents over 50 images with commentary relating to aspects of the transportation history of Smyrna and South Cobb up to 1870. Part 2, which will follow within the next few days, will carry the transportation history of the area forward to the present day. WPM

1. North Georgia Land Hunger and the Georgia Gold Rush, 1828-45

This 1839 map of Cobb County illustrates the centrality of Atlanta Road, linking Standing Peachtree, on the southern shore of the Chattahoochee River with the recently founded settlement of Marietta (the seat of Cobb County) in the former Cherokee Nation. Note that Terminus (as Atlanta was originally called) does not yet appear, nor is the route of the Western and Atlantic Railroad or the Smyrna Campground (the cradle of Smyrna) yet indicated. An ancient roadway, laid out by the natives of the area, Atlanta Road was the chief route by which pioneer settlers entered South Cobb and points north, many of them headed for the gold fields about fifty miles to the north of the site of Smyrna in and around what would later become Lumpkin County.

This 1839 map of Cobb County illustrates the centrality of Atlanta Road, linking Standing Peachtree, on the southern shore of the Chattahoochee River with the recently founded settlement of Marietta (the seat of Cobb County) in the former Cherokee Nation. Note that Terminus (as Atlanta was originally called) does not yet appear, nor is the route of the Western and Atlantic Railroad or the Smyrna Campground (the cradle of Smyrna) yet indicated. An ancient roadway, laid out by the natives of the area, Atlanta Road was the chief route by which pioneer settlers entered South Cobb and points north, many of them headed for the gold fields about fifty miles to the north of the site of Smyrna in and around what would later become Lumpkin County.

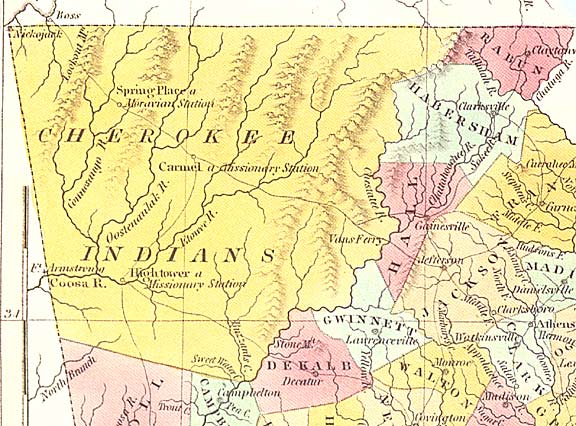

This earlier 1830 map showing the area north of the Chattahoochee River as then constituting part of the Cherokee Nation. The State of Georgia disputed tribal title to this land, notwithstanding treaties with both the state and federal governments. With the discovery of vast deposits of gold in North Georgia in 1828, leading to America’s first gold rush, pioneers flooded into this disputed area. Eventually, in 1838, the Cherokee were forcibly removed from North Georgia by the U.S. army troops in an incident known to history as “The Trail of Tears.”

This earlier 1830 map showing the area north of the Chattahoochee River as then constituting part of the Cherokee Nation. The State of Georgia disputed tribal title to this land, notwithstanding treaties with both the state and federal governments. With the discovery of vast deposits of gold in North Georgia in 1828, leading to America’s first gold rush, pioneers flooded into this disputed area. Eventually, in 1838, the Cherokee were forcibly removed from North Georgia by the U.S. army troops in an incident known to history as “The Trail of Tears.”

The home of Cherokee Chieftain James Vann (1766-1809), which still stands in Chatsworth, Georgia reflects the efforts that the Cherokee people made to adapt themselves to the life style of the whites. Vann, who was of combined native American and Scottish parentage, as many of the Cherokee leaders were, was a major planter, businessman, and a slave owner. The Cherokee were one of the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” of the southeastern United States. Of all the native tribes of that region they were the most noted for adapting themselves to white cultural practices, including development of a written language, adoption of a constitution and legal code of their own, and the establishment of a representative government headquartered at New Echota, about fifty miles north of Smyrna, etc., but the level of racial prejudice and outright land hunger and greed of the mass of white settlers trumped all such considerations, leading in due course to the expulsion of the Cherokee people from Georgia.

The home of Cherokee Chieftain James Vann (1766-1809), which still stands in Chatsworth, Georgia reflects the efforts that the Cherokee people made to adapt themselves to the life style of the whites. Vann, who was of combined native American and Scottish parentage, as many of the Cherokee leaders were, was a major planter, businessman, and a slave owner. The Cherokee were one of the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” of the southeastern United States. Of all the native tribes of that region they were the most noted for adapting themselves to white cultural practices, including development of a written language, adoption of a constitution and legal code of their own, and the establishment of a representative government headquartered at New Echota, about fifty miles north of Smyrna, etc., but the level of racial prejudice and outright land hunger and greed of the mass of white settlers trumped all such considerations, leading in due course to the expulsion of the Cherokee people from Georgia.

Cherokee Chief James Vann

Cherokee Chief James Vann

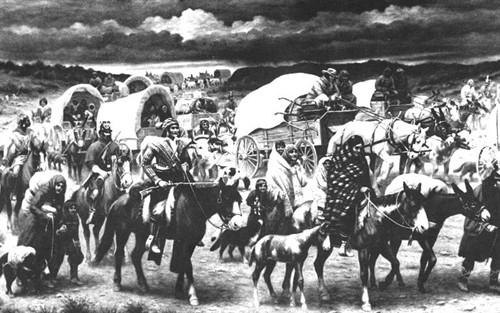

The forced removal of the Cherokee in 1838, in the winter months,under army escort, to the trans-Mississippi region, in present-day Oklahoma.

The forced removal of the Cherokee in 1838, in the winter months,under army escort, to the trans-Mississippi region, in present-day Oklahoma.

A typical pioneer wagon of the period.

A typical pioneer wagon of the period.

A miner panning gold in North Georgia. The quality of the gold found in the hills of North Georgia was of an especially high quality.

A gold coin minted in Georgia

When the former Cherokee Nation was divided into counties by the state of Georgia in 1832, the southernmost component was given the name “Cobb County” Since, at this point, it was not yet clear where in North Georgia deposits of gold might be found, most of Cobb County was distributed to settlers in 40 acre (gold prospecting) rather than 160 acre (farming) allotments. Cobb County was found, however, to contain no gold deposits of any significance.

The 1832 Cherokee Land Lottery determined title to the mining and farmg parcels distributed of the former Cherokee Nation. Native Americans, it should be noted, were not eligible to participate in the lottery.

An 1832 land lottery certificate for a 40-acre parcel of land situated in the present Vinings area issued to one Alexander Patterson.

An 1832 land lottery certificate for a 40-acre parcel of land situated in the present Vinings area issued to one Alexander Patterson.

The home of Thomas Hooper, a pioneer settler of South Cobb.

The richest single resident of South Cobb in the early years was Hardy Pace, the founder of Vinings. Pace’s career offers an excellent example of how the area’s entrepreneurial element accumulated significant wealth in the early years. Notably, the founder of Vinings acquired the bulk of his wealth from non-agricultural ventures, such as operating a gristmill, ferrying passengers across the Chattahoochee River (as seen in this illustration), and hiring out his slave force (the largest in the county) to work on public works projects.

The Montgomery Ferry, 1837. Two wheeled vehicles of the day are depicted in this illustration: a wagon transporting hay is being conveyed across the Chattahoochee while another, drawn by oxen and carrying a pioneer family awaits its turn to cross over the Chattahoochee into Cobb County.

The Montgomery Ferry, 1837. Two wheeled vehicles of the day are depicted in this illustration: a wagon transporting hay is being conveyed across the Chattahoochee while another, drawn by oxen and carrying a pioneer family awaits its turn to cross over the Chattahoochee into Cobb County.

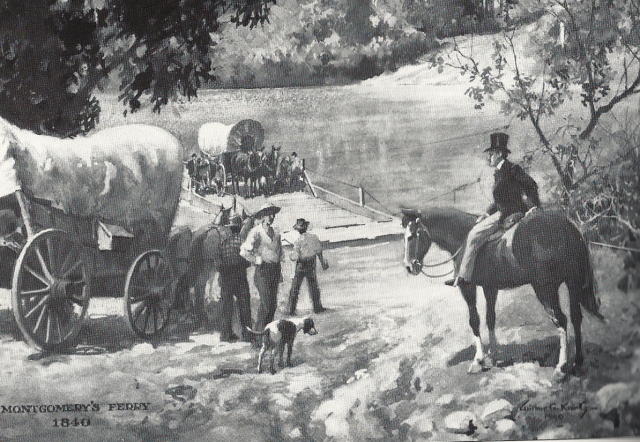

A second view of the Montgomery Ferry dating from 1840 is shown here. Both of these illustrations were created by artist and historian Wilbur Kurtz. This second one depicts ferry owner James McConnell Montgomery, the founder of Buckhead, on horseback supervising the operation of the ferry he operated on the river, one of several that conveyed pioneer settlers across the formidable Chattahoochee River, into Cobb County in the early years.

A second view of the Montgomery Ferry dating from 1840 is shown here. Both of these illustrations were created by artist and historian Wilbur Kurtz. This second one depicts ferry owner James McConnell Montgomery, the founder of Buckhead, on horseback supervising the operation of the ferry he operated on the river, one of several that conveyed pioneer settlers across the formidable Chattahoochee River, into Cobb County in the early years.

2. Smyrna: A Religious Campground

The Smyrna Campground was established at an indeterminate point in the late 1830s or early 1840s by the Methodists of the area. The campground serves as a gathering point for religious services in a day when Methodist preachers rode circuit and made irregular visits to such religious gathering points in that as yet sparsely settled district. The Smyrna Campground was situated near the intersection of present day Atlanta Road and Church Street, just south of the site where Smyrna’s Market Village now stands.

The Smyrna Campground was established at an indeterminate point in the late 1830s or early 1840s by the Methodists of the area. The campground serves as a gathering point for religious services in a day when Methodist preachers rode circuit and made irregular visits to such religious gathering points in that as yet sparsely settled district. The Smyrna Campground was situated near the intersection of present day Atlanta Road and Church Street, just south of the site where Smyrna’s Market Village now stands.

An itinerant Methodist preacher on his way to a campground or church in the North Georgia wilderness.

An itinerant Methodist preacher on his way to a campground or church in the North Georgia wilderness.

An artist’s conception of what the original Smyrna brush arbor at the Smyrna Campground might have looked like. This structure is said to have stood on a parcel of land at the southeast corner of Smyrna’s Church and King Streets.

An artist’s conception of what the original Smyrna brush arbor at the Smyrna Campground might have looked like. This structure is said to have stood on a parcel of land at the southeast corner of Smyrna’s Church and King Streets.

The most distinguished of the various clergymen who preached at the Smyrna Campground was the Reverend George Foster Pierce (1811-1894). The published history of Smyrna’s United Methodist Church tells us that this leading religious figure, who later served as President of Emory College and as a Methodist bishop, often preached under the Smyrna brush arbor and in the log Methodist Church, adjacent to the Smyrna Memorial Cemetery, that was built on the campground in 1846.

3. The Western & Atlantic Railroad: A Revolution in Cobb County Transportation, 1839-51

An early map showing the projected route of the Western & Atlantic Railroad that would eventually link the newly created settlement at Terminus (later renamed Atlanta) at its southern extremity to the Chattanooga, Tennessee and to the nation at large.

An early map showing the projected route of the Western & Atlantic Railroad that would eventually link the newly created settlement at Terminus (later renamed Atlanta) at its southern extremity to the Chattanooga, Tennessee and to the nation at large.

Stephen Harriman Long, an army officer who led several important exploring expeditions in the Rocky Mountains region earlier in his career, was hired in 1837 by the State of Georgia as Chief Engineer to oversee the construction of the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Disagreements with his employers led to his dismissal in 1841.

Stephen Harriman Long, an army officer who led several important exploring expeditions in the Rocky Mountains region earlier in his career, was hired in 1837 by the State of Georgia as Chief Engineer to oversee the construction of the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Disagreements with his employers led to his dismissal in 1841.

Stephen Harriman Long, Chief Engineer of the W&A, is shown here driving a stake into the ground to mark the southern terminus of the line, this being the point where a major American city, Atlanta, would shortly arise, in an illustration by Wilbur Kurtz.

The role railroads played in the rise of Atlanta, which was by the 1850s the terminus of no less than four railroads, is reflected in the railroad motif of the seal of the Atlanta City Council.

The role railroads played in the rise of Atlanta, which was by the 1850s the terminus of no less than four railroads, is reflected in the railroad motif of the seal of the Atlanta City Council.

The Western & Atlantic Engineering Office in Atlanta, erected in 1842. An illustration by Wilbur Kurtz.

The Western & Atlantic Engineering Office in Atlanta, erected in 1842. An illustration by Wilbur Kurtz.

Hauling of the engine “Florida,” 1842. The “Florida” was the first locomotive to arrive in Terminus. It was hauled 68 miles by wagon and mule from Madison, Georgia, then the end of the Georgia Railroad, which was also in process of construction.

Hauling of the engine “Florida,” 1842. The “Florida” was the first locomotive to arrive in Terminus. It was hauled 68 miles by wagon and mule from Madison, Georgia, then the end of the Georgia Railroad, which was also in process of construction.

The first train to operate on the Western & Atlantic Railroad line did so in December 1842. At that point the line extended only from Atlanta to Marietta, a distance of about 20 miles. Not until 1851 would the W&A be completed all the way to Chattanooga. Among the passengers on that first train was a nine year old girl named Rebecca Latimer, who 60 years later, under her married name, Rebecca Latimer Felton, would become the first female United States Senator.

Another notable traveler on the W&A almost twenty years later was Jefferson Davis, on his way to Montgomery, Alabama to be inaugurated as the first President of the Confederate States of America. Historic accounts tell us that Davis passed through Smyrna in the early hours of the morning. Upon reaching Atlanta, he stopped at the Trout House Hotel, where he delivered a rousing speech in defense of the South.

Here we see a portage wagon climbing Chetoogeta Mountain just north of Dalton, Georgia. The W&A Railroad, 137 mile long, had to span four major rivers and a mountainous terrain. No single physical obstacle presented a greater problem than Chetoogeta Mountain. The engineers resolved this difficulty by boring a 1,146 foot long tunnel through this formidable barrier, the last major physical obstacle to the completion of the line, a project that took the better part of a year to complete In the intervening period freight and passengers had to be hauled over the mountain as depicted in this illustration.

Here we see a portage wagon climbing Chetoogeta Mountain just north of Dalton, Georgia. The W&A Railroad, 137 mile long, had to span four major rivers and a mountainous terrain. No single physical obstacle presented a greater problem than Chetoogeta Mountain. The engineers resolved this difficulty by boring a 1,146 foot long tunnel through this formidable barrier, the last major physical obstacle to the completion of the line, a project that took the better part of a year to complete In the intervening period freight and passengers had to be hauled over the mountain as depicted in this illustration.

Tunnel Hill on the W&A line, at Chetoogeta Mountain

With the completion of the W&A all the way to Chattanooga in 1851, a telegraph line was installed as a safety precaution. Initially the W&A was a single track line, with sidings provided to avoid collisions. One such siding long existed at East Spring Street in Smyrna. The significance of the installation of the telegraph should be emphasized. Not only did it ensure much greater safety, it also integrated North Georgia into the nation’s communications grid. Information that previously had taken days to reach locations could now be conveyed almost instantaneously.

Here we see Atlanta’s pre-Civil War main Railroad Depot, which will be burned in the aftermath of the Battle of Atlanta. Note the number of horse-drawn vehicles gathered in the vicinity of the depot carrying diverse products to Atlanta to be trans-shipped to distant markets.

Here we see Atlanta’s pre-Civil War main Railroad Depot, which will be burned in the aftermath of the Battle of Atlanta. Note the number of horse-drawn vehicles gathered in the vicinity of the depot carrying diverse products to Atlanta to be trans-shipped to distant markets.

The W&A integrated North Georgia into the nation’s economic fabric. The railroad carried a wide range of local products to points of distribution both at its southern extremity (Atlanta), linked with southern railroad lines, and at its northern end (Chattanooga), tied to an even faster growing network of northern and western lines. By the time of the Civil War, the State of Georgia, had the most extensive system of railroads in the deep south, none more important than the W&A. Among the more important products transported on this line were the mineral and timber resources of North Georgia and the great southern staple, cotton, for which there was a huge demand in the north where a burgeoning cotton textile industry was developing.

Map showing the links between the W&A and the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railroad (the NCSL line), linking the W&A to Memphis and points west.

Map showing the links between the W&A and the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railroad (the NCSL line), linking the W&A to Memphis and points west.

An early train transporting both passengers and cotton to Market.

An early train transporting both passengers and cotton to Market.

The importance of cotton to the local economy is evident in this photograph of downtown Marietta in the late 19th century. At that point Smyrna was little more than an agricultural village, still very much in the economic orbit of nearby Marietta.

The importance of cotton to the local economy is evident in this photograph of downtown Marietta in the late 19th century. At that point Smyrna was little more than an agricultural village, still very much in the economic orbit of nearby Marietta.

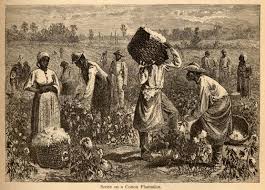

Cotton long continued to be the single most valuable commodity transported on southern railroads. Cotton was, indeed, the “king” of the southern economy.

Cotton long continued to be the single most valuable commodity transported on southern railroads. Cotton was, indeed, the “king” of the southern economy.

Western & Atlantic Railroad currency, issued during the Civil War, receivable in payment of taxes and all other obligations by the State of Georgia, 1862.

Western & Atlantic Railroad currency, issued during the Civil War, receivable in payment of taxes and all other obligations by the State of Georgia, 1862.

5. Effects of the Atlanta Campaign, 1864

In 1864 a well-equipped federal force of more than 100,000 invaded North Georgia with the object of weakening the war-making capacity of the state. The principal bone of contention in this campaign was control of North Georgia’s principal economic life-line, the Western & Atlantic Railroad. This struggle culminated in the September 1864 fall and burning of the City of Atlanta, the second largest metropolis in what remained of the Confederacy at that point by forces under the command of General William Tecumseh Sherman. The significantly outnumbered Confederate army under General Joseph E. Johnston followed an essentially defensive strategy in opposing the Federal juggernaut pulling back time after time.

Generals Sherman and Johnston, the Union and Confederate commanders in the Atlanta Campaign of 1864.

Generals Sherman and Johnston, the Union and Confederate commanders in the Atlanta Campaign of 1864.

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain was fought less than eight miles north of Smyrna. Confederate forces under General Johnston help back an effort by General Sherman’s federal forces to push the Confederates off of Kennesaw Mountain, an ill-considered assault that cost the Union Army 3000 lives. However Johnston soon after abandoned this impregnable bastion continuing his retreat toward the critically important industrial and transportation nexus of Atlanta.

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain was fought less than eight miles north of Smyrna. Confederate forces under General Johnston help back an effort by General Sherman’s federal forces to push the Confederates off of Kennesaw Mountain, an ill-considered assault that cost the Union Army 3000 lives. However Johnston soon after abandoned this impregnable bastion continuing his retreat toward the critically important industrial and transportation nexus of Atlanta.

The fighting on the Smyrna Line. Here Confederates forces initially held the line, but as had been the case of Kennesaw Mountain, the outnumbered Confederates abandoned this line and moved south.

The fighting on the Smyrna Line. Here Confederates forces initially held the line, but as had been the case of Kennesaw Mountain, the outnumbered Confederates abandoned this line and moved south.

View of a temporary trestle constructed by Union forces across the Chattahoochee River at Bolton, Georgia in 1864. The original W&A Railroad bridge at that location had been destroyed by the Confederates during their withdrawal to Atlanta. A steam passenger car is visible at the extreme right.

View of a temporary trestle constructed by Union forces across the Chattahoochee River at Bolton, Georgia in 1864. The original W&A Railroad bridge at that location had been destroyed by the Confederates during their withdrawal to Atlanta. A steam passenger car is visible at the extreme right.

Many local residents fled the area in advance of the arrival of the Union forces, encouraged to do so by Johnston’s army. Some of them took passage on the W&A and interlocking rail lines to the south. Private residences more often than not survived the fighting, whereas manufacturing facilities, such as the Concord Woollen Mill at Mill Grove (some three miles southwest of downtown Smyrna) which manufactured cloth for confederate uniforms, and the cotton mills at nearby Roswell, were torched.

Ruins of the Concord Woolens Mill, at Mill Grove on Nickajack Creek, southwest of Smyrna

Ruins of the Concord Woolens Mill, at Mill Grove on Nickajack Creek, southwest of Smyrna

General Sherman sees Atlanta for the first time from the top of Vinings Mountain

General Francis Asbury Shoup, a brilliant Confederate military engineer, designed the six mile long Riverline defense system just north of the Chattahoochee River. This bastion, sometimes referred to as “the Maginot Line of the Confederacy,” was intended to shield the retreating Confederate army and also enable them to flexibly responsd to Union efforts to cross the river and advance upon Atlanta. As I suggested in an article posted elsewhere on this blog, in choosing not to use the Riverline defense system, Johnston’s army may have lost its last opportunity to halt the Union advance and thereby save Atlanta. Johnston decision to cross the river resulted in his dismissal by President Davis as commander and replacement by the more aggressive General John Bell Hood.

One of the 36 interconnected forts or “shoupades” that comprised the six-mile long Riverline defense system.

One of the 36 interconnected forts or “shoupades” that comprised the six-mile long Riverline defense system.

Union troops crossing the Chattahoochee River in pursuit of the retreating Confederates.

Union troops crossing the Chattahoochee River in pursuit of the retreating Confederates.

The Battle of Atlanta, seen here, with General John Bell Hood now in command. Despite fierce resistance, Atlanta fell to the Union Army on September 2, 1865, an event that one recent historian characterized as “The Death of Dixie.”

The Battle of Atlanta, seen here, with General John Bell Hood now in command. Despite fierce resistance, Atlanta fell to the Union Army on September 2, 1865, an event that one recent historian characterized as “The Death of Dixie.”

The systematic destruction of Atlanta’s manufacturing capacity and railroad facilities by the Union army is underway in December 1864 as Sherman prepared his “March to the Sea.”

The systematic destruction of Atlanta’s manufacturing capacity and railroad facilities by the Union army is underway in December 1864 as Sherman prepared his “March to the Sea.”

Destruction of the WA tracks and associated buildings near Atlanta

Destruction of the WA tracks and associated buildings near Atlanta

It is well to remember the critical role that slave labor played in the construction of major public works projects in Georgia. The massive Riverline Line defense system, built near the northern Shore of the Chattahoochee, was erected by a force of about 1000 slaves sent up from the Atlanta area, many no doubt by train. The defensive network was built over a period of weeks.

It is well to remember the critical role that slave labor played in the construction of major public works projects in Georgia. The massive Riverline Line defense system, built near the northern Shore of the Chattahoochee, was erected by a force of about 1000 slaves sent up from the Atlanta area, many no doubt by train. The defensive network was built over a period of weeks.

A force of African-American convict laborers at work on the W&A line. After the war African-Americans (many of them convicts) provided much of the labor that helped reconstruct and maintain the W&A Railroad as well as other major public works projects.

A force of African-American convict laborers at work on the W&A line. After the war African-Americans (many of them convicts) provided much of the labor that helped reconstruct and maintain the W&A Railroad as well as other major public works projects.

While the railroad made stops at sidings in Smyrna from 1842, not until 1869 was a railroad depot built at Smyrna. While we have no picture of the original Smyrna Depot, which stood several hundred feet north of the East Spring Street intersection, it probably resembled the Kennesaw depot, pictured here, which was built in 1870.

End of Part 1

The Chattahoochee River is where at least 32 ethnic groups came to live in the 1700s. They assimilated to become the Creek Indians by the end of that century. Two thousand years before then one of the earliest known permanent, agricultural towns, north of Mexico, was founded along its bank. In the zone where a series of cascades mark the boundary between the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain, there is a Mississippian town site at least as old as Ocmulgee National Monument. Downstream are many town sites with mounds, dating from the period from 950 AD to 1600 AD.

In between the nerdy information about our past, there are tidbits in this edition, that will have you saying, “Oh my gosh!” We will let you in on dirty little secrets from over 40 years ago that explain some strange events in recent years. The Chattahoochee is destined to reveal many more secrets in the future.

From its source in the mountains to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico, it is about 542 miles long. The Chattahoochee begins as a spring on the east slope of Georgia’s Brasstown Bald Mountain, about 1500 feet south of the source of the Hiwassee River, which flows to the Tennessee River, and about 16 miles east of the source of the Coosa River, whose waters eventually reach Mobile Bay. Its first thirty miles is within Georgia’s gold bearing district.

LikeLike